Minor Calendars

by Valens

Calendars, I am told, fall into four major categories: lunisolar, solar, lunar, and seasonal. Amidst the vast array of human experience, this may appear to be a limited number of major categories at first. To me, all seem to pose a common question: how does one reconcile the lunar cycle with the solar cycle?

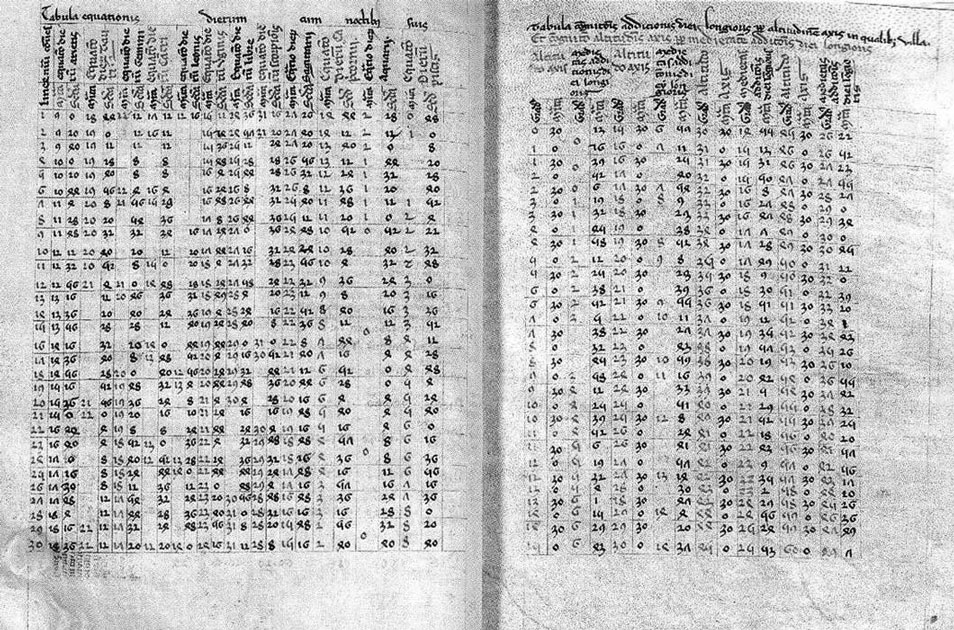

The Alfonsine Tables provided data for computing the position of the Sun, Moon and planets relative to the fixed stars. The tables were named after Alfonso X of Castile, who sponsored their creation. Source: Public Domain.

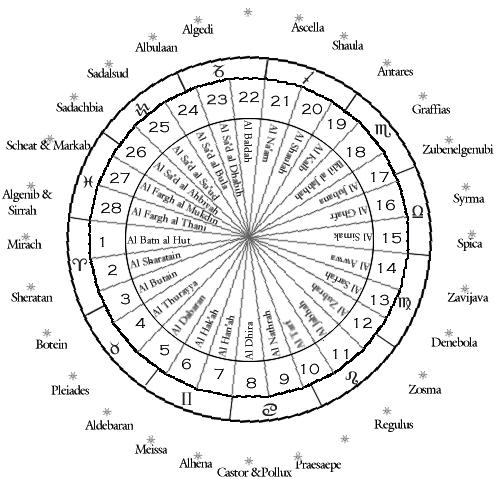

Early calendars often ground astronomical cycles in a third observable phenomenon: the stars. The stars featured greatly in how Indian, Arabic, and Chinese astronomers marked the passage of the moon across the sky. The moon takes slightly more than twenty-seven days to return to the same location in the sky. For each of these days, the moon can be observed close to, that is a “conjunct” of, a particularly bright star. While differing across regional cultures, with some using twenty-seven and others using twenty-eight, these stars construct what can be thought of as a lunar zodiac. Just as the sun passing through parts of the sky demarcated by stars creates “Taurus”, “Scorpio”, or “Aries” — monthly periods with narrative characteristics — the moon passing through parts of the sky demarcated by stars similarly creates daily periods with narrative characteristics. Thought of quite literally as residences, the lunar mansions, as astronomers called these daily periods, provide the moon with temporary yet familiar abodes.

Source: https://www.yeatsvision.com/Mansions.html.

For example, the star Aldeberan, a red star serving as the bull’s eye in the Taurus constellation, creates the fourth lunar mansion. Aldebaran gives off a strong, steady light, and therefore in myths indicates a fixity of purpose. When the moon resides in the lunar mansion of Aldeberan, Indian Vedic astrology recommends building or demolishing a house. The eleventh-century Arabic text the Picatrix recommends, for the strangely aesthetically inclined among us, to “take red wax and from it fashion the image of an armed man riding a cavalry horse holding a serpent in his right hand.” Beyond creating a quality of time, each lunar mansion creates a quality of action: a type of talismanic transaction that should be undertaken. While some of us typically rest on Sunday, others may be busy creating wax statues.

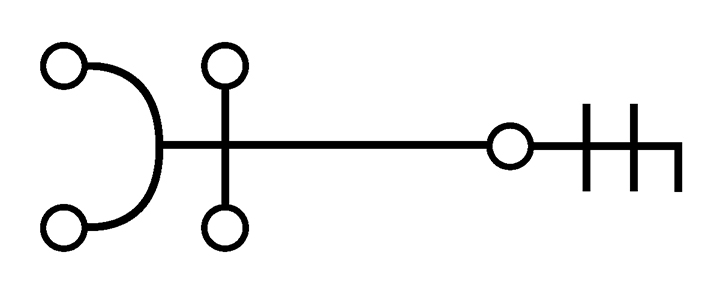

The symbol for Caput Algol, a star in the Perseus’ constellation, with the symbol originally described by Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. Source: Selket, May 27, 2007, GNU Free Documentation License, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Algol_symbol_(Agripe_1531).svg/.

The lunar mansions proved to be enduring calendars over millennia. Their endurance can be linked to their observability. The relative fixity of the stars combined with the mutability of the moon, both available through visceral nightly observations, support a notion of vernacular time. Though it can indicate seasonal shifts in its longer cycles, this vernacular time cannot be directly linked to production, unlinked as it is even those phases of the moon. Whereas solar calendars, even ones anchored on seasonally rising stars, largely revolve around cycles of sowing, harvesting and reaping, the lunar mansions persist through art forms and gossip, across cultures and centuries, by which suggesting what course of action may prove best. They are more useful for conspiracy than extraction.

The earth’s orbit around the sun will never be neatly divisible by the moon’s orbit around the earth — forever escaping mechanically-perfect timekeeping. In the discrepancy between the lunar and solar calendars and thus inductive and productive action, we see many attempts to reconcile two cycles that can never be fully commensurate, neither numerically nor functionally. Mediated by the stars, they have inspired their own zodiacs and convey their own notions of right action.

If calendars can be seen as attempts to reconcile cycles, timekeeping systems can be seen as attempts to harness them within a political economy. The Ottoman Empire tried to ban mechanical clocks to prevent the secularization of time. The Spanish colonists burned the Mayan codexes that were instrumental for timekeeping. A French politician recently called for the “nationalization of time,” in perhaps a paltry echo of 1793, when French Revolutionaries reset the formerly Christian calendar to year zero and enforced a new timekeeping system focused on intervals of ten. Today, labor struggles persist around the reclamation of time. As Giordano Nanni writes in The Colonization of Time:

“Time has remained the single most important issue in labor disputes... with demands for shorter working days in the nineteenth century leading to the Factory Acts, Bank Holidays Acts, and the forty-hour week and in the twentieth century, to paid-overtime and time-off ‘in lieu’. The definitive step had already been taken, however, from the moment at which workers began to talk about time, work and wages in the language of the clock, consenting to fight -- as E.P. Thompson famously put it -- ‘not against time, but about it’.”[1]

While easily dismissed as a fantasy from a middle-class science-fiction novel, the malleability of timekeeping is not a thing reserved for past empires. Just as the ship invented the shipwreck, every technology acting at a societal scale invents its own time.[2] The establishment of Greenwich Mean Time, our globally-dominant form of timekeeping, did not emerge directly from a nation state but from the Railway Clearing House, ushering in what became informally known as “railway time.” Current technologies that invent time often try to wrestle it away from more irregular structures, such as atomic timekeeping that forgoes measuring the earth’s orbit for measuring an atom’s frequency. Still, we have not fully articulated the concept of “internet time,” despite how the technology increasingly weaves its way into the social fabric. There have, however, been interesting proposals for networked-time machines.

While the history of networked-time machines likely begins at 00:00:00 UTC on 1 January 1970, Unix time has yet to reach escape velocity as a timekeeping system itself. Most people know of public blockchains as a technology supporting cryptocurrency, but the Bitcoin whitepaper makes a more broadly interesting case for their innovation: the provision of a “distributed timestamp server.” with the term “timechain” in its code comments.[3] One problem Bitcoin sought to solve, the double-spend problem, can be seen not only as a forgery of value but also more deeply as a forgery of time — the attempt to say that the same unique action can occur more than once. Blockchains try to produce a continuous stream of discrete transactions and through this attempt to produce shared history become a form of time machine. They affectively create a sense of time that is both continuously, linearly propagated and discretely mapped through transactions. Despite intentional, accidental and hypothetical forks, blockchains seem to carry with them implicit agreements on canon; participants in the network generally convey the legitimacy of one blockchain fork over another. The ability to sever time exists, though it remains difficult to do with impact. Going beyond atomic clocks and Unix time, which seek to regulate an abstract sense of time already present within society, blockchains create their own abstract sense of time, which, to this date, largely facilitates economic transactions. When combined with transparency, meaning that the public can access all records of transactions, blockchains become a rigid force of transactional time: block time. “Blockchains never forget.” We see their hegemonic shape rise over the hill, beginning to institute total surveillance of transactions as the norm.[4] Transparent blockchains create a sense of time that is linear, regular and unforgiving.

In contrast to transparent blockchains, shielded blockchains facilitate transactions that are private by default, but can be verified by the initiator. While implementations differ, shielded blockchains allow participants agency in their submission to block time. They can form free associations with other participants and without onlookers. While still contributing to a time machine with the linear and discrete at its core, the nature of their participation becomes neither immediately clear nor reasonable. Shielded blockchains create a sense of time that is about revelation.

In the vein of what Deleuze and Guattari called minor literature, we can loosely think of shielded blockchains in the context of minor calendars.[5] That is, minor calendars unanchor language, connect an individual to a political immediacy and allow for collective utterances. The political immediacy strikes at a moment when we realize total surveillance appears to many as a given, instead of the brief and new historical phenomenon that it is. Through private yet verifiable transactions, shielded blockchains act as a necessary counterpower to total surveillance through digital technologies. As a minor calendar, they let one pseudonymously speak as many. They retain irregularity in their timekeeping system: some, but not all, transactions in discrete blocks could be revealed, when necessary, with discretion. The labor movement may have lost something when its struggles became “not against time, but about it.” In this case, the minor calendar does not say which transactions should be public. It is about being against surveillance, instead of being about particular instances of it.

Source: Nicholas Roerich, Flame of Happiness (Lights on the Ganges), 1947, State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow, Russia, Public Domain.

If transparent blockchains find their analog in solar calendars and shielded blockchains find their analog in lunar calendars, we find a useful and productive irreconcilability between the two — a state in which most political hope usually lies. Counterpowers need lore to persist; they need their own timekeeping. Like the lunar mansions, the latter's stories come from interpersonal observation, peer-to-peer and non-transparent interactions, from gossip in the night. As suggested before, solar and lunar calendars separately convey their own notions of right action. And it is in the dark, where talismans are crafted, that responsibility for right action takes on its true importance.

Notes

- Giordano Nanni, The Colonisation of Time: Ritual, Routine and Resistance in the British Empire (Manchester University Press, 2012), 42. ↩

- Paraphrasing Paul Virilio, Politics of the Very Worst (New York: Semiotext(e), 1999), 89. ↩

- Cryddit, "Bitcoin source from November 2008.", Bitcoin Forum, December 23, 2013, https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=382374. ↩

- Venkatesh Rao, "Blockchains Never Forget", Ribbonfarm, May 25, 2017, https://www.ribbonfarm.com/2017/05/25/blockchains-never-forget/. ↩

- Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (University of Minnesota Press, 1986). ↩

Preorder the third issue printed version

Preorder the third issue printed version